Where Technology meets Archaeology

It is large, red, and drives around the field on its own in search of archaeological traces no one can see. No, it's not part of the Transformers universe, but an entirely new type of ground-penetrating radar robot. This spring, archaeologists from NIKU are using a revolutionary new technology to search for unknown cultural heritage sites. The technology promises increased efficiency, environmentally friendly solutions, and more accurate mapping of cultural heritage sites underground.

Collaberation combining archaeological expertise with cutting-edge technology

AutoAgri AS is a technology company based in Trøndelag that develops and manufactures self-driving electric equipment carriers for agriculture, parks, and construction.

Guideline Geo/MALÅ, based in northern Sweden, is a leading technology company focused on geophysical measurement equipment and is a supplier of ground-penetrating radar technology.

NIKU is an independent research and competence center for Norwegian and international cultural heritage. NIKU works on the development and use of high-tech solutions in archaeological surveys.

Over the past weeks, this newly developed system, called AutoMIRA, has been deployed in the historically rich landscapes of Vestfold County for field tests and the first proper archaeological surveys. These tests served multiple purposes: to identify and resolve minor equipment issues, to develop new fieldwork routines, and to train NIKU’s personnel who will operate the system in the future.

Robot on the hunt for cultural heritage

The test sites were selected in collaboration with archaeologists from the Vestfold County Administration to address current challenges in cultural heritage management.

As the main test site Heimdalsjordet, located some 500 m south of the famous Gokstad Mound in Sandefjord municipality was chosen. It is in this mound that one of the best-preserved Viking ships, the Gokstad Ship, was found.

“On this field, a trading place from the Viking Age has previously been identified,” says project leader Erich Nau from NIKU. He is one of Norway’s most experienced ground-penetrating radar experts.

“We have driven several times in the same place with different types of ground-penetrating radar equipment since 2011. Now we can compare the new data with the old ones and see how significant the improvements are.”

The Intersection of Technology and Archaeology

In the evolving field of archaeology, the intersection of technology and archaeology is an exciting frontier, where innovative tools and methods are transforming how we explore and understand the past. One such groundbreaking advancement is the integration of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) technology into archaeological fieldwork.

The development of AutoMIRA, a groundbreaking initiative at the intersection of technology and archaeology, showcases the collaborative efforts between NIKU (Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research), AutoAgri AS, and Guideline Geo/MALÅ. This partnership not only draws on past experiences from the previous LBI-ArchPro project but also taps into current international collaborations with the Vienna Institute for Archaeological Science (VIAS, University of Vienna) and Geosphere Austria. Together, these partnerships fuse deep archaeological expertise with cutting-edge technology to push the boundaries of cultural heritage research.

“We are incredibly proud of what we have achieved together,” says Knut Paasche from NIKU. Paasche is the head of the Digital Archaeology department at NIKU and a driving force behind the development of the new ground-penetrating radar.

“This is a great example of how interdisciplinary collaboration brings about innovative solutions.”

AutoMira: A Paradigm Shift in Fieldwork

AutoMIRA has the potential to revolutionize archaeological surveys. Unlike traditional methods where archaeologists manually operate GPR equipment, AutoMIRA is a fully autonomous machine equipped with a high-resolution, multi-channel GPR system. This allows it to navigate terrain independently, collecting data with unprecedented efficiency and accuracy.

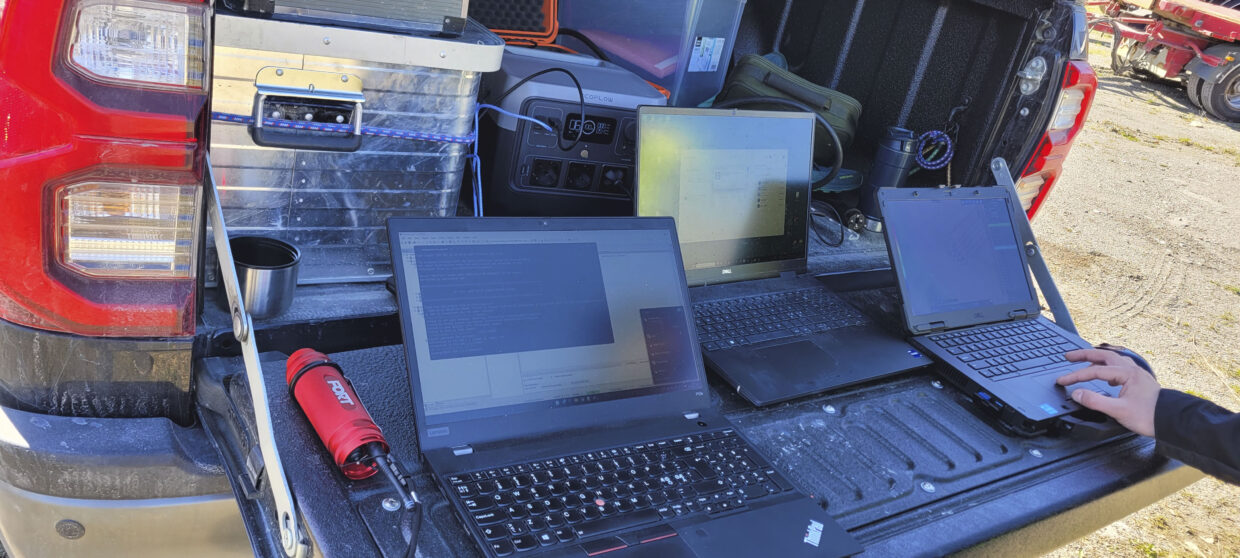

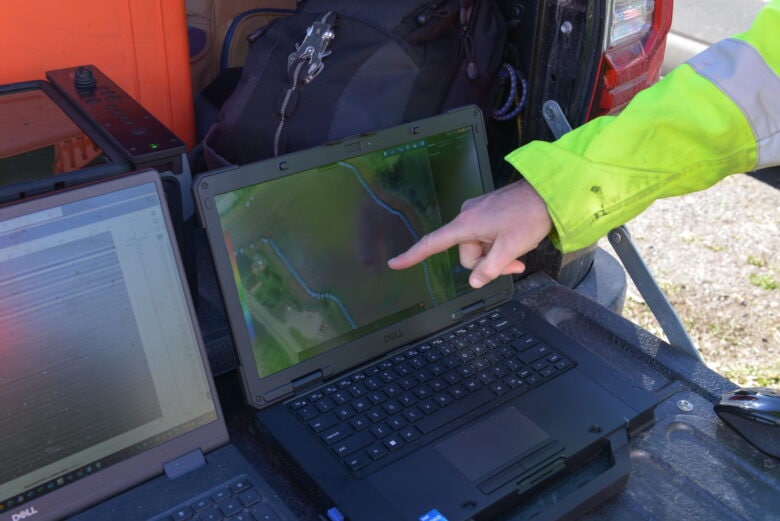

The new survey workflow begins with pre-survey mapping, where AutoMIRA’s routes are programmed using aerial imagery and a manual mapping of the field boundaries to ensure comprehensive coverage. During the survey, the system autonomously navigates these predefined routes while archaeologists can monitor the robot’s progress remotely. Simultaneously, the collected data is available for preliminary analysis.

“Previously, archaeologists themselves would drive the ground-penetrating radar equipment around the field. Now, we only need a small amount of time to set up the system and the route, then the machine handles the rest on its own,” says Nau.

Designed with sustainability in mind, AutoMIRA operates on a fully electric power system, significantly reducing carbon emissions and noise compared to traditional fuel-powered survey equipment. This shift towards a more automated and data-driven approach enhances survey efficiency, promising to open new avenues in the exploration of cultural heritage sites and entire cultural landscapes.

Applications and Implications

The implications of this technology are profound. By scanning the subsurface without excavation, AutoMIRA can detect hidden objects, structures, and features buried beneath the ground, providing archaeologists with a non-invasive means of exploration akin to taking an X-ray of the soil.

The potential applications are vast. From identifying prehistoric settlements and infrastructure to mapping burial sites and entire cultural landscapes, AutoMIRA opens new avenues for archaeological research. Its ability to cover large areas in a fraction of the time compared to manual surveys not only increases efficiency but also minimizes environmental impact—a crucial consideration in heritage preservation.

Beyond archaeology, AutoMIRA’s capabilities extend to soil science, where it can map soil properties to aid in precision agriculture, optimizing resource use and increasing sustainability. In geology, it allows for detailed sedimentology studies over extensive areas, supporting environmental assessments and planning. Furthermore, the ability to map existing drainage infrastructure with greater accuracy holds immense potential for more sustainable water management in agricultural fields.

Looking Ahead

The ongoing research and development collaboration exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary cooperation in driving technological innovation for archaeological purposes.

Looking forward, the team will continue to address issues identified during the initial field tests. Plans are already in place to transport AutoMIRA to Austria during the summer for further field tests and demonstrations in collaboration with our Austrian partners. These activities will not only enhance the system’s capabilities but also expand its application scope, ensuring that AutoMIRA can meet a variety of field conditions and research demands, thereby solidifying its role as a transformative tool in archaeology.